Quality testing and testing quality

What do we really mean when we say quality? With this title, an article with interesting and relevant messages was published in the March issue of TEA-Time with testers, the international professional journal of IT testers.

Should we focus on the product or the process?

What do we really mean when we say quality? With this title, an article with interesting and relevant messages was published in the international professional journal of IT testers, Tea time with testersin the March issue of the publication.

How does your team or company measure quality? — asks the author of the article, testing expert Janet Gregory, consultant to DragonFire Inc., author of numerous IT professional publications and publications. The former raises another problem concerning the relationship between measurement and quality: he believes that people often tend to equate testing with quality (or quality assurance), but it is by no means certain that good testing practices automatically guarantee the high quality of the product. In Gregory's work, he finds that many teams “only” measure the quality of each process during testing, and they don't even realize that they are simply forgetting the essence, i.e., testing the quality of the product — even though it would be really important for the customer.

The expert warns: the quality of the process, of course, also affects the product, but the final result is also influenced by a number of other factors. That is why it is important to explore the links between the development process, which includes testing, and the quality measurements used by companies using different techniques. The author seeks to do this, that is, to investigate the interactions between process and product quality in his work. He stresses that quality assurance aspects must be integrated into development processes from the very beginning, and customer involvement is also essential.

Product quality

Although they have to be managed together in everyday life, it is still worthwhile to discuss the issue of product and process quality separately in the basics. So does Janet Gregory. Regarding product quality, he states that it is a very complex concept, which is difficult to define and formulate in practice. Gerald Weinberg, an American IT scientist, anthropologist and psychologist, defines it as “Quality is value to some person”. However, he adds that all this, placed in the context of testing, is not nearly enough, since - although fundamentally true - it oversimplifies the situation. In the case of most products, we do not know which dimension of quality is really important for a consumer. Testers need to know not only the process, but also the goals that the product is intended to achieve, since the key issue in assessing quality is how satisfied the end user is with the functionality of the product. Of course, it is not only the opinion of external (end), but also internal consumers that matter. Different divisions of the organization — such as product management, marketing, finance, etc. — may have different quality requirements for a given product, and these are also important aspects for testers. There are many other aspects that we must take into account when testing, Gregory emphasizes, and among them he highlights the generational differences that are increasingly significant in terms of product quality (consumer experience). He adds, however, that there is no right or wrong way of thinking in this area, only priorities diverge.

Process quality

According to the author of the article, a much more precise topic is the study of process quality, if only because the majority of organizations focus primarily on this area. In other words, the focus is mainly on how the quality of the tested processes, including testing, contributes to the final product quality. Gregory points out that by testing many people already mean testing the finished software or system, although ideally it takes place during the entire development, in all its phases. Testing provides feedback on the work done, reveals hidden defects, helps to identify and mitigate potential risks, provides information on the current state of the product, and also plays a prominent role in continuous quality monitoring. However, the expert emphasizes: testing alone does not guarantee quality, it only gives feedback about it!

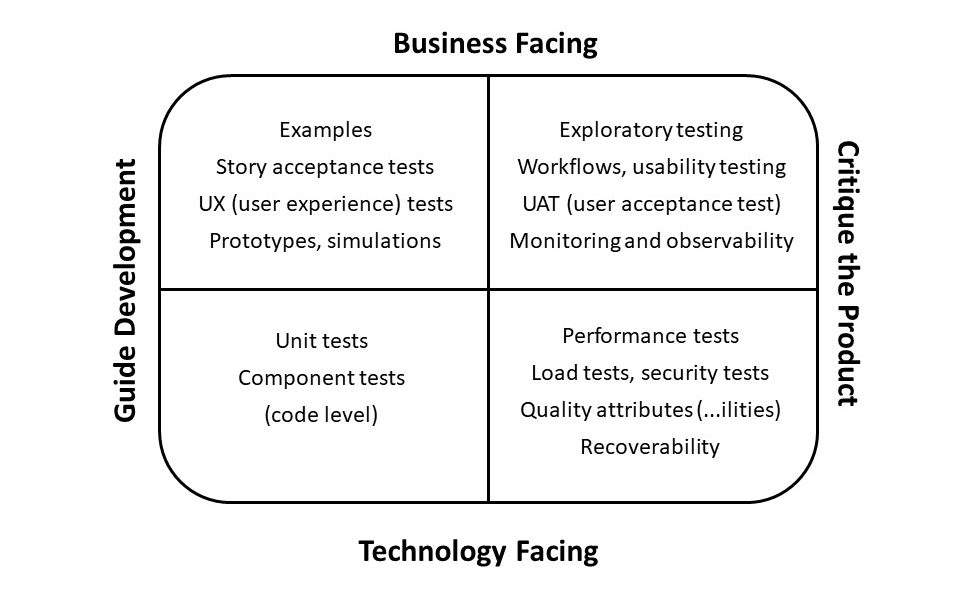

But how does examining different product and process quality dimensions work in practice? Janet Gregory illustrates all this in the following figure. As he says, this model is suitable for teams to schedule and make the testing process more efficient and transparent. While on the left you can see tasks before programming, on the right you can already see the test phases to detect coding errors and fix them as quickly as possible. Cost-effective operation and technologically relevant testing tasks at the bottom illustrate the interests and different perspectives of so-called internal customers (different organizational divisions) on the importance of testing.

As can be seen from the table, the expectations for testing are different in each area, so it is important to define the needs precisely at the beginning of the process. Gregory points out in this regard: the tester - even if he is an external one - must think like a team member and always make sure that he is looking for answers to the right questions and problems in his work! We need to think, for example, about the functional diversity that causes user diversity, that is: we need to know who, for what purpose and how (and then) uses the given product! When testing, this is all important.

Of course, testing does not end with the product hitting the market. Monitoring and monitoring the activity of the end user - of course in a pre-fixed and legal framework - allows teams to receive direct feedback on the operation of the product and the reactions of the user. These feedbacks are equally suitable for effective problem solving and for further product development and function expansion.

Measuring quality

The question, of course, remains: how will the data collected during testing and feedback become value, information about the quality of the product? Do we even know what to measure? The author states that although there are trivial findings (low quality is bad), the question is much more complex than relying solely on such generalities. In addition, it often happens that sometimes we accept a lower quality because it is cheaper, and it may be a better decision in a particular case than choosing a higher quality product.

A further dilemma in terms of quality measurement is that “poor” quality, for example, by the number and severity of defects, is much easier to determine than if something is of outstanding quality. For if the number of defects is zero, then it can be considered as the expected (ideal) quality; but then the question arises: what does good or excellent quality mean and, if there is such a category at all, by what criteria can we determine it?

The author of the article explains that while there are positive metrics for process quality (such as cycle time or processing rate), in terms of product quality it is already much more difficult to find them. In addition to testing, organizations are also using other, more creative methods: conducting customer satisfaction surveys and analyzing customer service activities related to a specific product. Customer return rates and loyalty can also be important feedback on a product or product range.

In the quality assessment, important information can also be extracted from the risk analysis data. This is a relevant aspect for both the process and the quality of the product, as the lower the risk of malfunction or product failure, the higher the quality. The dilemma of the negative-positive movement is of course also present here: ideally, neither the process nor the product conceals the risk of failure, and all other options can only affect the quality in a negative direction.

Conclusion

According to Janet Gregory, it can be said all in all: for good quality, it is not enough to make sure that the product works, but also to guarantee that all the customer's needs are met! At the very beginning of the testing work, it is important to clarify the quality requirements for the process and the product, as these basically determine what tests should be carried out and what risks should be focused on.

The author emphasizes that testing supports the achievement of good quality, but in itself is not a guarantee that the good quality of the process will not automatically approve the product. Quality is extremely complex and diverse, so for each product it is necessary to define the expectations associated with it individually! Achieving good quality is both an organizational and an individual responsibility. It can only be achieved if the needs of each division are clear, as well as all contributors (all members of the organization) are aware of what they need to do to produce a high quality product.